The Presence of Absence

Category: Bishop's Sermons

Speaker: The Rt Rev Mark D.W. Edington

Tags: presence, absence, all saints

Just last week we heard those old comforting words from the Wisdom of Solomon, at least those of us who were at the annual Convention of the Convocation. We heard them because we decided to make our service of Evening Prayer on the Friday of Convention a service of remembrance for all those who have been affected by this miserable season of a pandemic virus—those who have died, those who have suffered, those who have mourned, those who have endured the loss of jobs, or security, or homes, or mental health.

Chers amis, je suis très reconnaissant et très heureux d’être parmi vous cet après-midi. C’est ma première visite à Saint-Esprit et pourtant j’ai beaucoup entendu parler de vous. Je sais que la pandémie du Covid a été particulièrement dure pour votre communauté, notamment parce que cela signifiait que nous devions nous passer de musique pendant longtemps.

Mais Dieu vous a donné la force de garder espoir, et maintenant nous voici réunis. Je sais que vous pouvez dire au son de ma voix que le français n’est pas ma langue maternelle, et je suis sûr que vous m’entendrez faire beaucoup d’erreurs aujourd’hui. Veuillez me pardonner; je vous suis donc reconnaissant pour nous accueillir Judy et moi et pour votre bienveillance et votre patience à mon égard.

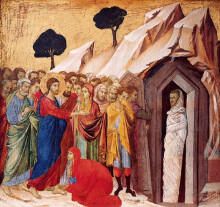

Aujourd’hui, c’est la Toussaint. L’histoire que nous entendons parle de Jésus, qui arrive trop tard à la maison de Béthanie où vivent Marie, Marthe et Lazare. Du moins, c’est ce que pense Marie.

Mais rappelez-vous les tout premiers mots que nous avons entendus aujourd’hui dans la lecture du Livre de la sagesse ; “Les âmes des justes sont dans la main de Dieu.” Jésus n’était peut-être pas physiquement dans la maison avec Lazare lorsqu’il est mort ; mais à aucun moment Lazare a été séparé du soin, de l’amour, de la protection de Dieu.

Quand nous parlons des saints dans nos vies, nous parlons de personnes qui sont présentes pour nous, présentes dans nos vies, surtout quand on a parfois l’impression que Dieu ne l’est pas.

Dieu peut sembler absent, pourtant Dieu nous est toujours présent par le Saint-Esprit. Le Saint-Esprit vit en chacun de nous qui avons été baptisés.

Et Dieu est présent parmi nous, dans chacun des membres de notre communauté, dans notre église, qui nous aime et prend soin de nous. Ce sont les saints que nous avons. Et ce sont les saints que nous sommes.

Il n’y a donc pas de meilleur endroit pour célébrer la Toussaint qu’une église nommée Saint-Esprit. Car c’est par l’Esprit Saint que Dieu est toujours présent avec nous. C’est le Saint-Esprit qui agit à travers les amis qui prennent soin de nous, les gens qui sont des saints pour nous. Et c’est le Saint-Esprit qui agit à travers nous, nous rendant capables d’être des saints pour les autres.Five million people have perished because of Covid. We can’t count how many others may have died because their own health needs could not be attended to by overcrowded hospitals, or because feckless leaders in some countries denied the fact and severity of this disease for their own purposes.

We are spiritual people. Whether life brings us hardship or joy, tears or laughter, our instinct is to bring it to prayer. That used to be a generally shared reflex across most people in our culture. Now, it is something more like a specialization.

But for those of us who have that instinct, we have been living in a kind of suspended spiritual animation. It’s still difficult for me to grasp the long period during which loved ones could not be at the side of a family member who was dying, or even the smallest community could not gather to mourn.

I don’t know about you, but I feel as though we’ve missed part of our lives living through a time that we couldn’t do the basic human things. Gather for celebrations. Baptize new Christians. See each other’s faces across a room, instead of on a screen. Shake hands at the peace.

The worst of it has been the prolonged absences from people we love. We are so used to moving freely; we forget that for the vast majority of human history, it simply wasn’t so easy to travel, or explore, or to go to be with people we love at distances from us. What we take for granted is really a remarkable and rare thing. But suddenly it was taken away from us, and the absences became deep and empty.

We missed a lot in those absences. I wonder what you missed. I missed a chance to have one last visit with my closest mentor before he died last May. I would guess that most of us had at least one similar loss. The disconnection of absence has been hard on us.

Jesus is, in the most literal sense, absent from the scene in Bethany when Lazarus dies. The whole text of the story makes it clear that this absence is intentional on Jesus’s part; it’s not forced on him by circumstances like ours. He receives word that Lazarus is failing, and he choses, purposefully, not to go.

That is not something Mary and Martha know. All they know is Jesus is absent when their brother dies. They know how close their friendship had been. In part they are grieving for Jesus’s loss, and not just their own. And the fact that Jesus was absent by intention does not mean he feels no sorrow. Here for the only time in the whole New Testament, the account gives us a revealing two-word report that has perplexed scholars for centuries: “Jesus wept.”

I don’t want to engage that debate, which in any case is not very edifying. Instead I want to suggest that Jesus’s absence is something like the too-solid alibi that makes the detective in the story suspicious. It is almost as though Jesus was at pains to prove to everyone around him—even to Lazarus himself—that he was absent from the scene. Is it just possible that his alibi is too good?

Let’s go back to the text we started with. It begins this way: “The souls of the righteous are in the hands of God; and no torment will ever touch them.” And it ends this way: “He watches over his elect.”

That doesn’t sound like absence, does it?

Many of us have experienced the absences of our loved ones, the absences of people from our communities, as the symptom of something deeper and even a little terrifying—the absence of God. Where has God been in the midst of all this? This is more than a little bit like our own struggle with the problem of theodicy: How could a good God permit all this disaster to happen, and be absent from the scene of our suffering—maybe even, like Jesus, intentionally absent?

But to see it that way is to fall for the too-perfect alibi. It’s to believe that the apparent absence is in fact an abandonment. But that is not the case. Jesus never abandons Lazarus. And God is not absent from the scene.

Instead we are confronted with another of the paradoxes that shapes our faith. The first will be last. The least will be the leaders. The ones we marginalize—and we all marginalize some folks—will be the center. And God’s apparent absence, more often than not, discloses God’s presence.

Sickness and death do not separate Lazarus from God’s love. Mourning does not separate Mary and Martha from God’s love. Jesus’s exaggerated absence from the scene is something more like a holy sleight-of-hand, to convince everyone in the audience that he couldn’t possibly have been there.

But of course God was there. There in the ministrations of those who cared for Lazarus when he was dying. There in the support of neighbors and friends who would not let those two sisters grieve alone.

A lethal virus does not separate us from God’s love. Lockdowns and isolation do not separate us from God’s love. Fear and uncertainty do not separate us from God’s love. When people all around the globe are living through the temptation to despair that God is permanently absent, that is the moment at which we who are disciples should most be on the looking for God’s presence.

God has been present in the sheer courage of hospital workers and first responders who have put themselves in the direct presence of this disease in order to get us all through it. God has been present in the ingenuity and tirelessness of researchers who have sought better ways to treat this pernicious disease and possibilities to protect us against it.

God has been present in the faithful, devoted, determined parish leaders who have figured out where to put the phone for the best angle, how to make sure folks at home can hear what’s going on, and how to keep up the work of pastoral visitation even when actually visiting hasn’t been possible.

And now, as our attention turns this week from virus and pandemic to climate and biodiversity, God is present in the voices of those raising our sense of urgency about our planet.

God is present in the skills of those whose science helps us understand both how we got here and what we must do to repair the damage we have all caused.

God is present in the appeals of those who remind us that the seduction of nationalism is the greatest temptation we face in summoning the will to work collectively as a people with a common destiny on a single planet.

In every one of those cases, God’s presence is mediated through our friends, our neighbors, our fellow-Christians. God’s presence is mediated through our doctors, our scientists, even through our political leaders to whom has fallen the unenviable responsibility of designing the policies to get us through this.

Those are the saints we know. Those are the saints we are. We are God’s presence in a world convinced of God’s absence. Others have been that presence for us, and today we give thanks for them, and for being a part of a church that takes its identity from following their example.

And we pray that we, each one of us, may be given the grace to be the presence of God’s love, God’s hope, God’s encouragement, God’s transformation, in the lives of others, too. Amen.